So….

…a long-promised (and once-postponed) visit to Venice – and coinciding with Christmas 🙂

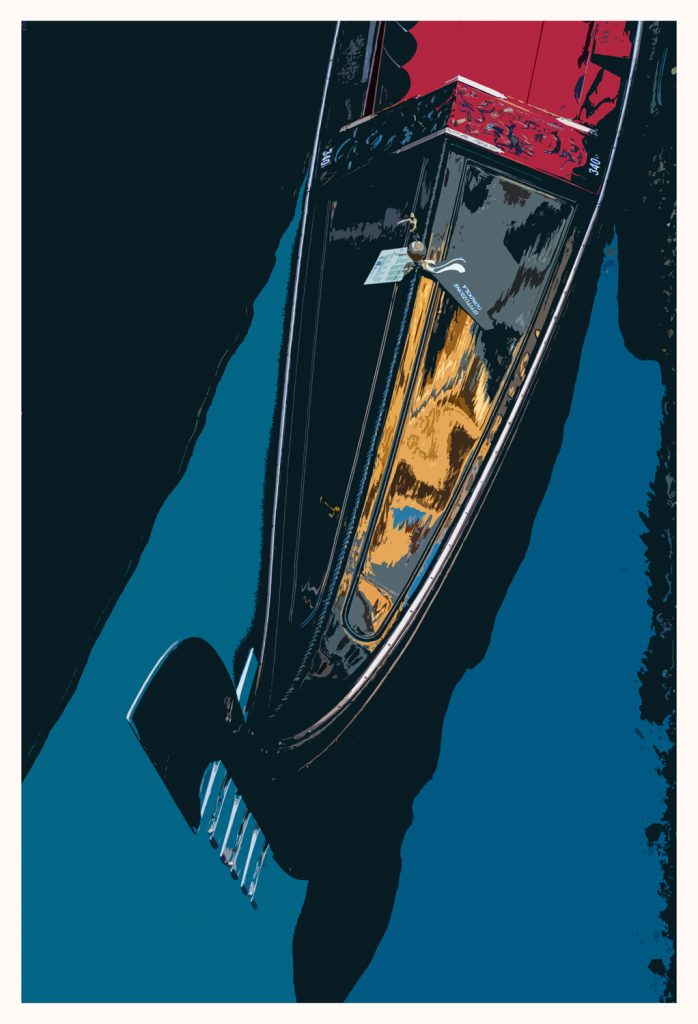

Arrival at midnight was something of an adventure as we were staying on the island of Murano. The whole business of reaching the island after the daily vaporetto service had shut down for the night (indeed perhaps for the Christmas season?!) had seemed a rather daunting challenge while sitting on the coach from Treviso Airport, but at that time of night, in freezing temperatures, it felt like we’d landed on our own surreal magic carpet when we stepped straight on board a private water taxi. Under the circumstances the 70 Euro fare seemed like a complete bargain, and there was no denying it was a beautiful boat with gorgeously varnished wood and royally plush seating in the deliciously warm cabin:

The surreal theme continued as we coasted along dark canals past even darker alleys:

By this time, daughter had the heebie-jeebies, and as we eventually blasted out past gaunt posts into the black lagoon she was far from happy…

It was therefore with a sense of considerable relief all round that we not only arrived at the island of Murano, but were dropped off right outside our hotel by our incredibly helpful taxi-driver:

Weirdness continued as we walked to the hotel entrance (and I had to remind myself that Murano was the glass-making island):

Unreality continued as were led to our room down the most astonishing corridor I have ever experienced, the ceiling higher than some cathedrals while the decor seemed more Morocco than Murano:

And so exhausted to bed, after first marvelling at the beauty of our room.

Next morning the external architecture of the hotel resumed the surreal theme by apparently placing us in ‘The Mystery and Melancholy of a Street’ by di Chiciro:

Nature, however, re-asserted normality when we were greeted at the canal-side by a curious black-necked grebe (Podiceps nigricollis) in winter plumage:

The journey across the lagoon to Venice was an utterly different experience from the previous night’s voyage, with the distant snow-covered Alps, the brilliant sunshine, turquoise lagoon and the clanking of the vaporetto engines (which sound as though they can only last about two weeks a piece, given the treatment they are subjected to):

Meanwhile the sleek private water taxis slid by on their way to Murano:

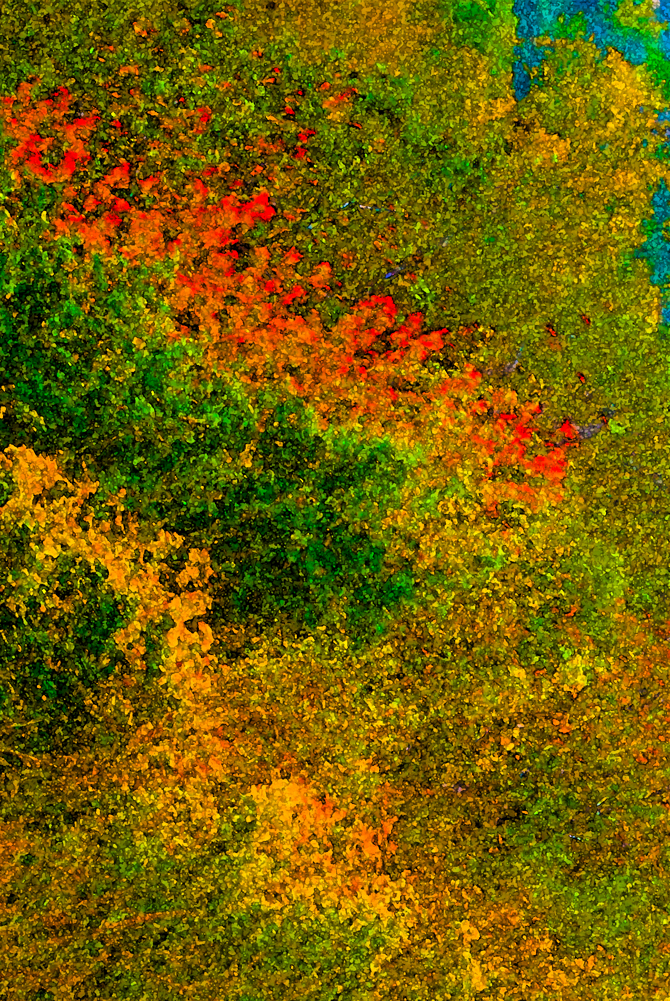

As for Venice itself… Well, ‘extraordinary’ doesn’t do it justice. The bright winter sun just seemed to make all the colours glow, aided by the reflections from the turquoise water:

The water taxis purr past while the vaporettos (in the background) thrash and grind their way round the canals:

Meanwhile the gondolas dance and weave like slow ballerinas:

Some of them really are quite sumptuous:

…and some have added biodiversity richness:

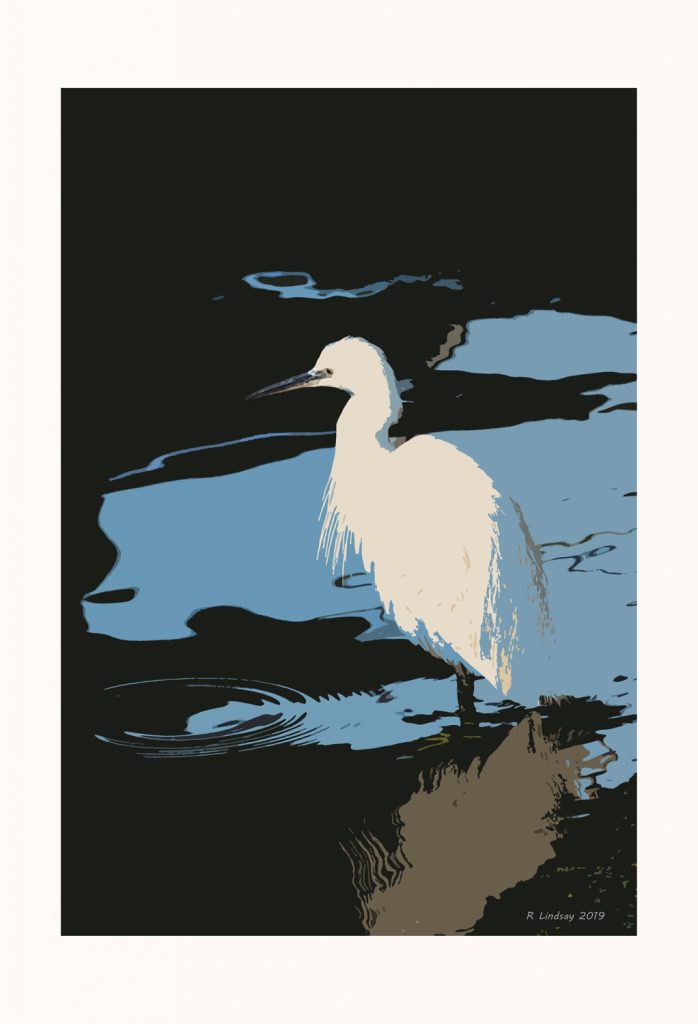

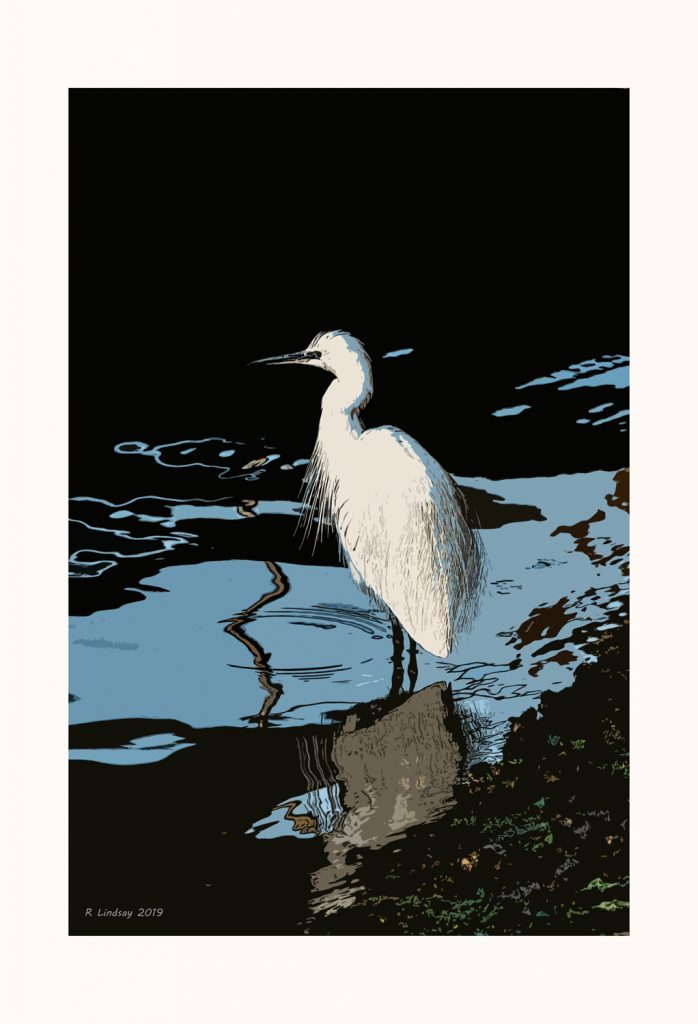

Indeed the grebes, egrets, yellow legged gulls, black headed gulls and pigeons all seem to take the hustle and bustle of the city in their stride:

This egret looked like it was wading in black Japanese lacquer:

San Marco square is indeed suitably impressive:

…but it’s the view from the waterfront there, over the gondolas out towards the Venetian island cemetery, that is one of the iconic images of Venice:

Sunset brings further transformation:

Heading from the square back to the peace and quiet of Murano gives yet another perspective, this time from the water:

Next day was spent exploring the maze of callas or alleyways which pass for ‘main streets’ in Venice:

Evening brought us back to San Marco and our favourite ‘hot chocolate’ cafe, as clouds began to gather and threaten a damp day ahead:

On the way back to our vaporetto stop we stumbled across “the most beautiful bookshop in the world”. Definitely the most remarkable bookshop I’ve ever visited. And just to emphasise that you are in Venice, it even has a gondola full of books:

…and I have to say I found the most amazing collection of material; even bought a rare but incredibly useful report about wetlands (daughter eye-rolling at this point)…

Next day was a shopping and museum day because the threatened drizzle had arrived. Murano looked even more like a place of the waters beneath the drizzle:

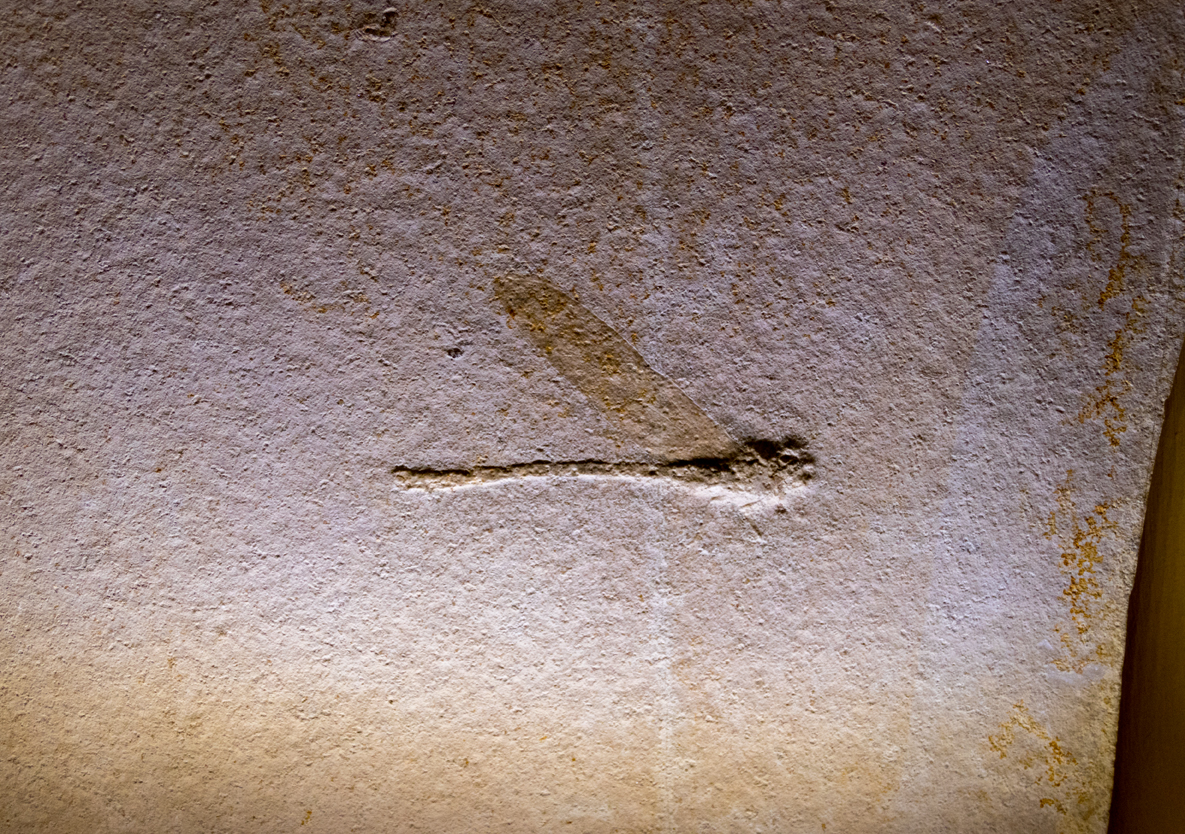

The Venice Natural History Museum was a delight, with some beautifully displayed material. Here’s a trilobite, with its tracks still preserved:

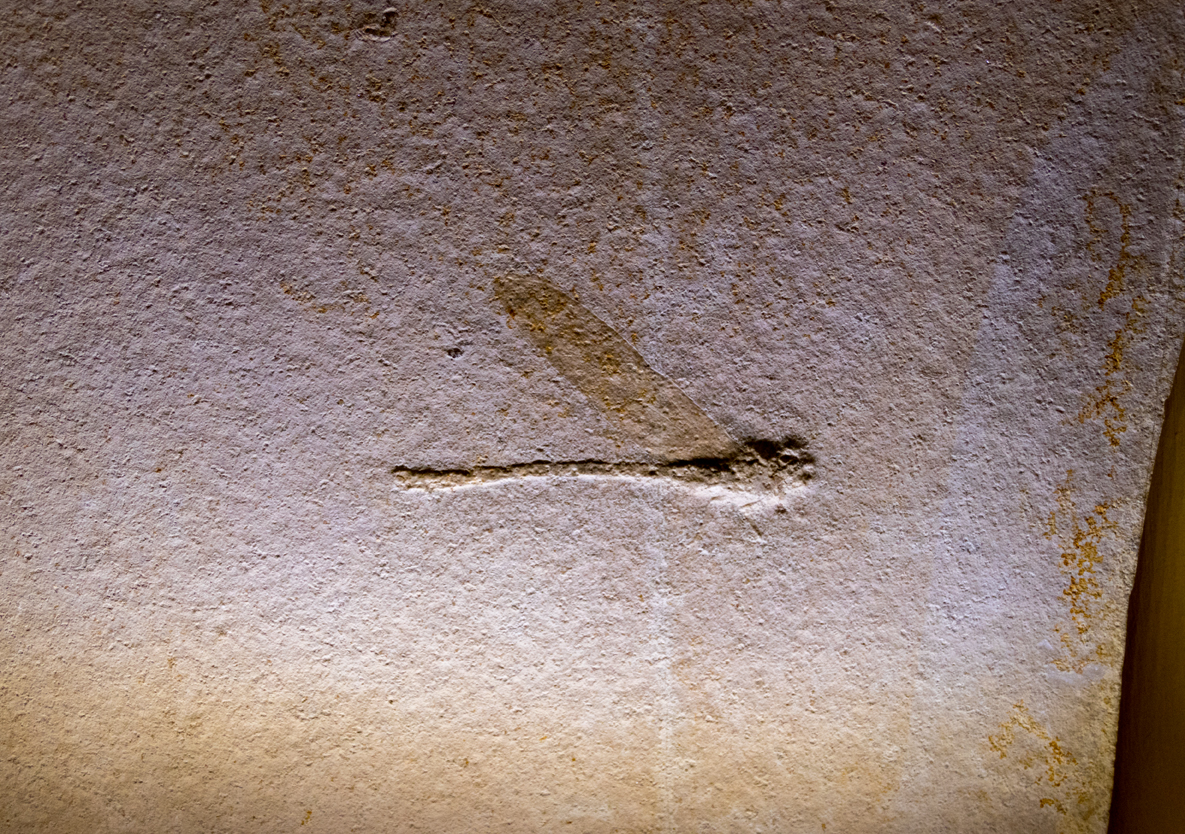

…and a delicate dragonfly from 350 million years ago, preserved in fine silt:

The exit atrium is dominated by this beautifully displayed blue whale skeleton (is this where London’s Natural History Museum got the idea from?):

The view from the Rialto bridge emphasized the thickening clouds:

…and by evening the rain was coming down fairly steadily, so we repaired to San Marco and our ‘hot chocolate cafe’ again:

The vaporetto back to Murano took on an eerie aspect when we passed a superyacht lit up like something from outer space:

…then being apparently stalked by a boat with an eerie blue glow, the eerieness in no way dispelled when it drifted close and waited, apparently empty as an abandoned spaceship, as we disgorged passengers at various stops without ever using those stops itself:

It drifted off mysteriously into the night as we headed into the darkness of the lagoon towards Murano, from where the Phare of Murano (lighthouse) was sending out beams which pierced the increasingly heavy squalls of rain:

For our final half-day we visited the Museum of Glass on Murano. I wasn’t expecting anything too thrilling but was keen to know why Murano had ended up as a glass-making centre. I emerged an hour later, none the wiser but deeply impressed by some of the glassware on display, and the videos of techniques are amazing. All this is done quite literally by brute-force artistry (glass is heavy and it’s necessary to work fast!). No clever machines involved at all, just human sweat and skill:

The less said about the journey home the better. Suffice it to say that this is the landscape approaching Beauvais (Paris) Airport, rather than Stansted (and a day later than booked), from which we had to make our own way back to Stansted (via crowded coach, crowded Eurostar, tube and train). Thanks, Ryanair…

However, Venice…? Quite extraordinary…!

Happy New Year 🙂