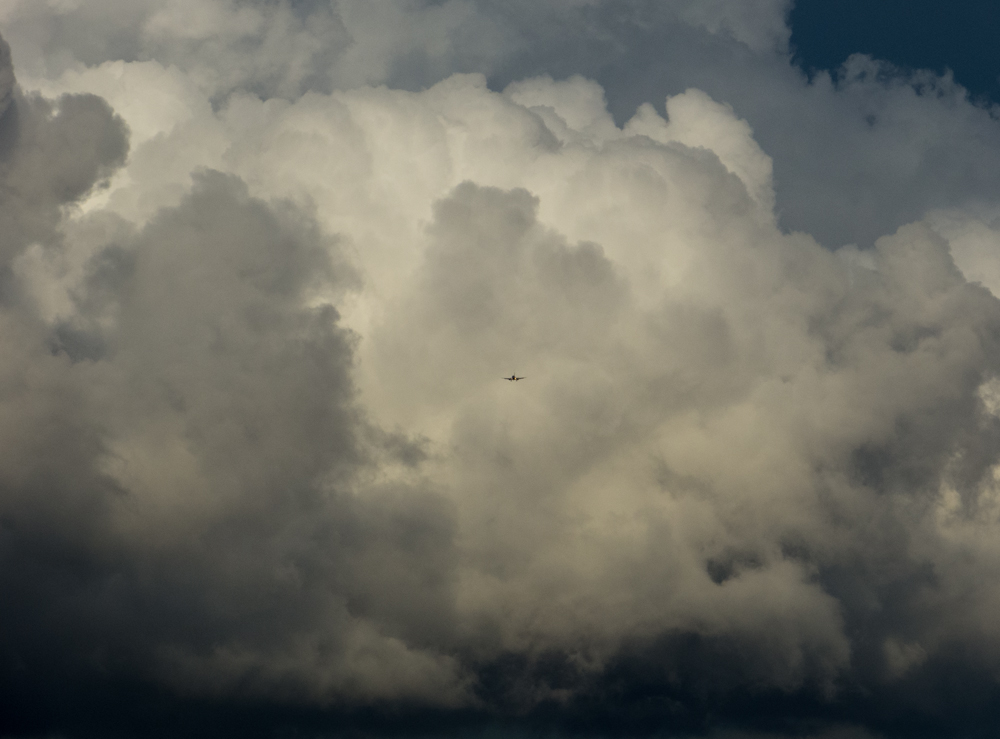

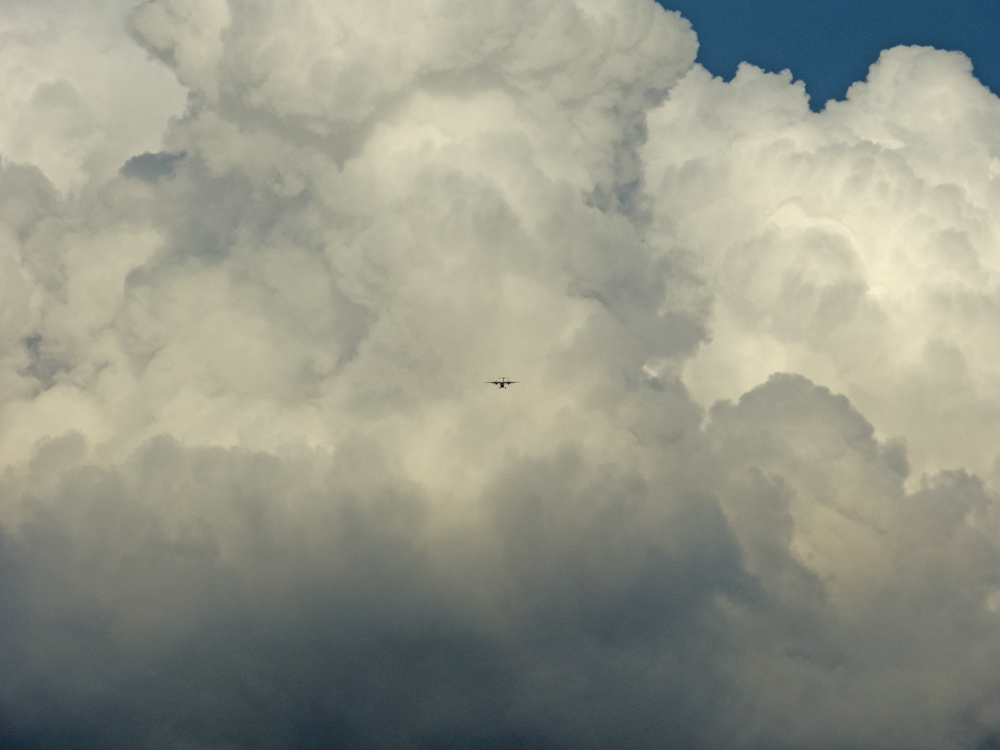

Up early again last Thursday, though not before dawn this time. The sky was looking rather interesting so it was a case of grabbing wellies, coats and cameras and heading off out into the fields. The sky was streaked with high cirrus (click on images for larger versions):

It feels distinctly as though the birdlife is more casual about human presence early in the morning. Blue-tits, blackbirds, great-tits all seemed largely un-bothered as I walked past:

Then I became aware that I was also being watched – by a normally-timid woodpigeon attempting to look like an ivy leaf:

Walking along the farm track there seemed to be a great deal of activity associated with a hedge up ahead, while the sky continued to do its cirrus thing:

A robin seemed to feel that it owned the hedge:

Meanwhile I was being scolded by a blue-tit who was busy hunting insects in the blackthorn flowers in the bushes behind me, although it decided against outright confrontation:

…when a flash of colour in the corner of my eye caught my attention. A jay flew into the same blackthorn bushes. It soon became obvious that it was flying back and forth between the field behind the blackthorn and a location some way down the hedge in front of me, carrying twigs for nest-building. Eventually I realised that there were two, operating in relays, and it was fascinating to watch the fact that they flew through the air like swimmers through water, giving a flap then gliding with wings against the body before flapping again. Approaching the nesting hedge they always did a spectacular braking flare:

Then suddenly all hell broke loose. The jays started screeching like a cockatoo with laryngitis, actually jumping up and down with anger, and I realised that a magpie had sneaked into their hedge from the far side, to investigate their nest. There was a huge amount of flapping, barging and swearing, until eventually the magpie fled into a nearby tree-top, chased by the jays. Eventually one of them looked down at me as if to say, “Well, what do you think of that? The cheek of it..!!”

Then to round off a thoroughly exciting early morning stroll, a pair of yellowhammers leapt out of the hedge as I was heading home and perched on the hedge-top, providing a lovely view of them:

…and so, home past the fields of sprouting wheat, then off to work…